Queerness on Salt Lake City’s Regent Street

“One cannot be pessimistic about the west. This is the native home of hope. When it fully learns that cooperation, not rugged individualism, is the quality that most characterizes and preserves it... then it has a chance to create a society to match its scenery.”

Salt Lake City’s Regent Street (formerly Commercial Street or Alley) was the center of the city’s newspaper printing business, Chinatown, and red-light district. Since the city’s growth, sin and debauchery were hosted within the interior streets and alleyways at the city blocks: out of sight, out of mind. Over time Regent Street hosted saloons, billiards lounges, barber shops, Chinese laundries and grocers, housing, and entertainment.

By 1903, Salt Lakers advocated cleaning up the sordid red-light district. By 1908 city leaders initiated the construction of the stockade: a “compound where the denizens could practice their inevitable trade freely, but discretely” (Balls). In the stockade, located behind today’s Gateway Mall, both prostitute and customer were closely regulated, and the red-light district of downtown Salt Lake City was gone (Balls, also Hallet Stone). Over time, generations of immigrant families left Regent Street and storefronts became vacant. In the early 2000s, the Salt Lake Tribune and Deseret News left their offices near Regent Street to downsize elsewhere. Regent Street became merely a business access road and back alleyway (Lee).

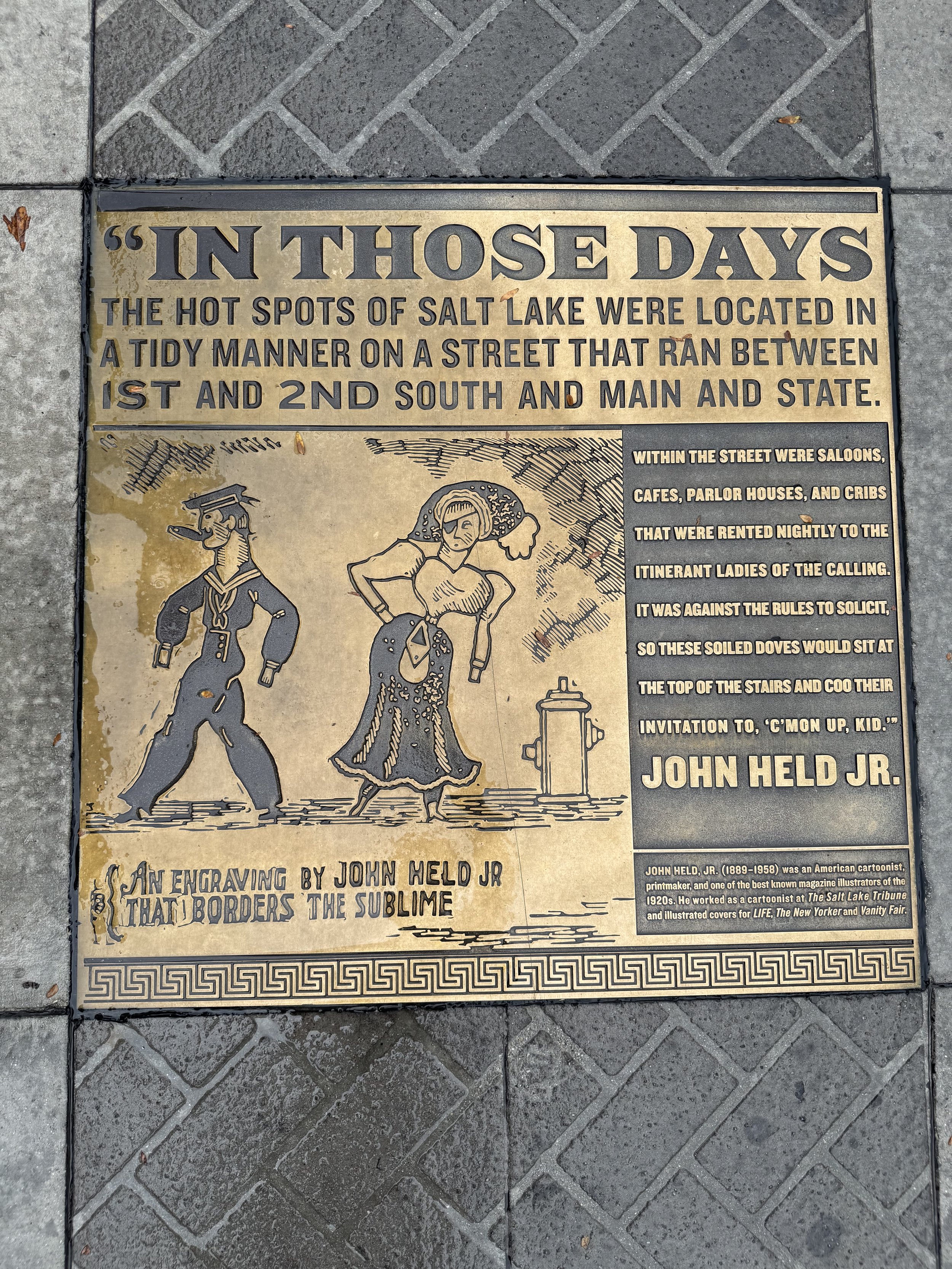

Marker on Regent Street in Salt Lake City highlighting the street’s former brothels (source: Randell Hoffman).

With the completion of the Eccles Theater in 2018, Salt Lake City officials created a “Regent Street Renaissance” and developed the street into something more for visitors, tourists, and nearby workers. The design by the GSBS architecture firm created an activated, human-scaled interactive space featuring restaurants, entertainment, parking, access to public transit, and educational enrichment.

In addition to the diverse histories highlighted in the beautiful markers on today’s Regent Street are stories of Queer and Trans lives.

William Burton + James Hamilton (not that James Hamilton)

On March 7th in 1891, William D. Burton and James Hamilton were arrested behind the Keystone Saloon for committing the “crime against nature” (The Ogden Standard-Examiner, 7 March 1891, p. 1). The Keystone Saloon backed up to what is now Regent Street in Salt Lake City. The Keystone Saloon is not in any existing city directories, but it was likely located where the public parking garage is at the south end and west side of the street (1889 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map of Salt Lake City, sheet 31). Several witnesses saw and reported the two men to the authorities, and they were promptly arrested. Hamilton’s identity cannot be officially confirmed, but he was likely a 24-year-old cook. Another James Hamilton of Salt Lake City existed, a 35-year-old LDS bachelor whose occupation cannot be determined. Burton was a 43-year-old ex-convict with a distinctive blue dot tattoo on the webbing between his index and forefinger. The tattoo is distinct because indicators of what we now label homosexuality or even for preferred sexual roles were not common in Utah but are more heavily seen in larger metropolitan areas (See: D. Michael Quinn’s Same-Sex Dynamics among Nineteenth-Century Americans: A Mormon Example, p. 284).

In March of 1891 they were tried by a “diverse” jury of members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saint and non-members which deliberated for over six hours. Because they were unable to break their own tie regarding a guilty verdict, the case was dismissed and tried again in May (Deseret News, 28 May 1891, p. 8.; also Deseret News, 29 April 1891, p. 10). In the meantime, Hamilton was held on a $2,000 bail, worth $2 million in 2025 (The Salt Lake Tribune,10 March 1891, p. 8). This jury, composed of all faithful Latter-day Saints, deliberated for five minutes and returned with a not guilty verdict (The Salt Lake Herald, 20 May 1891, p. 8; Deseret News, 27 May 1891, p. 8; and The Salt Lake Herald, 28 May 1891, p. 8). We do not know how or exactly why the second jury chose to find these men not guilty; detailed minutes were not created and court records only record the opening of the court session, a few major details about legal representatives in attendance, and the final outcome. This is, though, a demonstration of how identities that are so commonplace today, and marginalized in the past, were still intertwined in the U.S. west. As brief and arbitrary the story James and William may seem, they are just one of many stories which show how queer desire (in all its manifestations) survived under the shadow of criminalization.

Kenneth Lisonbee

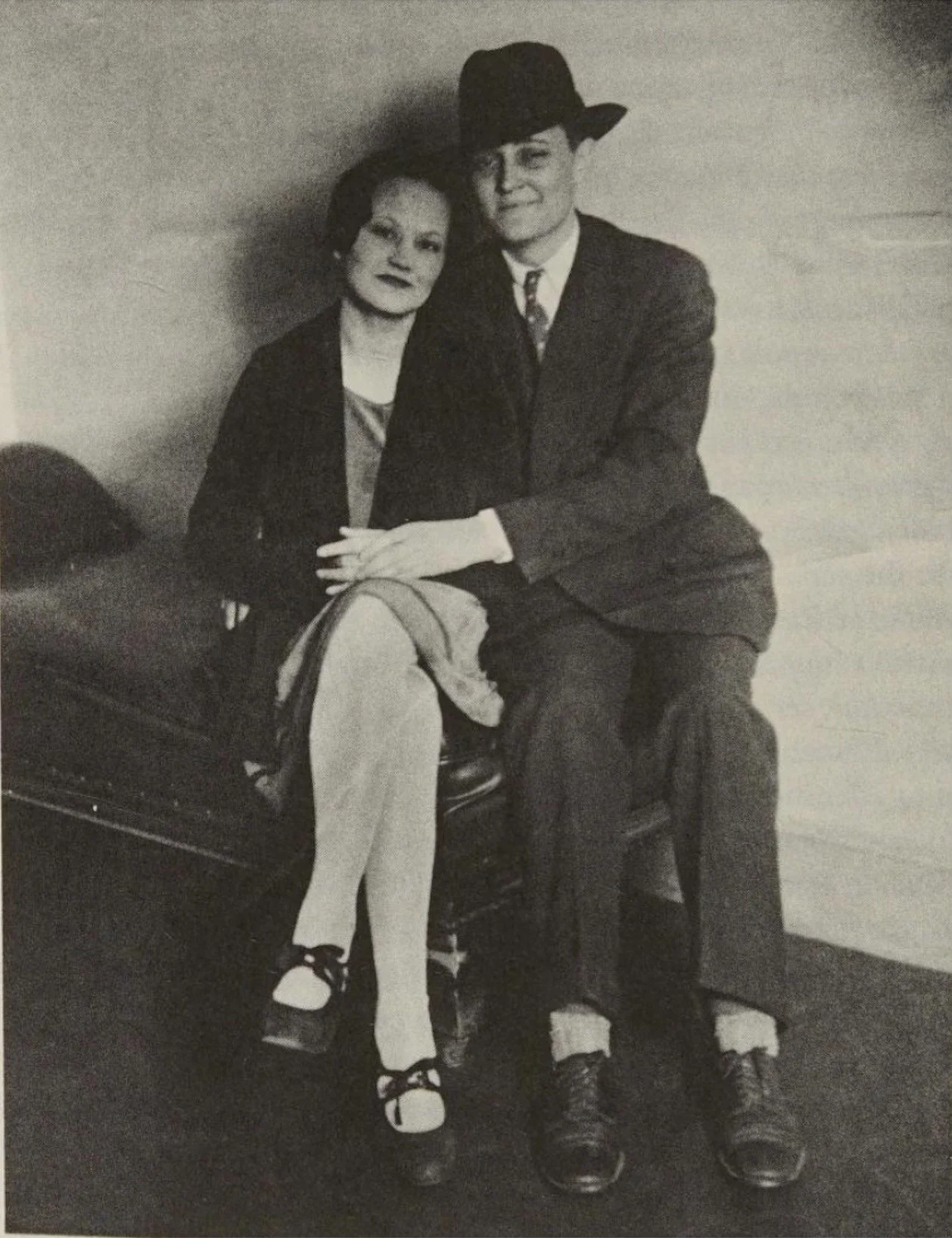

Colorado LGBTQ+ historian David Duffield recently notified board member and co-founder Connell O’Donovan of a discovery of a Utahn who defied gender norms throughout the twentieth century. Kenneth Lisonbee and Estella Harper are featured on the cover of "True Sex: The Lives of Trans Men at the Turn of the Twentieth Century" by Emily Skidmore (NYU Press, 2017). Connell O’Donovan shared their research so far on 25 August 2025:

‘Assigned female at birth, Kenneth "Kit" Lisonbee was born in Springville, Utah, just south of Provo, in 1903 and given the name of Katherine Rowena Wing. In the 1920s the Wing family moved to the mining town of Eureka. There Katherine began wearing men's clothing (to work on the family farm) and went by the nickname of Kit. A year after graduating from high school, Kit Wing moved to Salt Lake City and became a licensed barber apprentice. Kit worked at Albert Kramer's barber shop on Regent Street ... and boarded at the Kenyon Hotel, 211 S. Main. An uncle suggested that men would respond better to her barbering if she dressed as a man again, which she did. Taking the name of Kenneth Wing, he began living full time as a man.

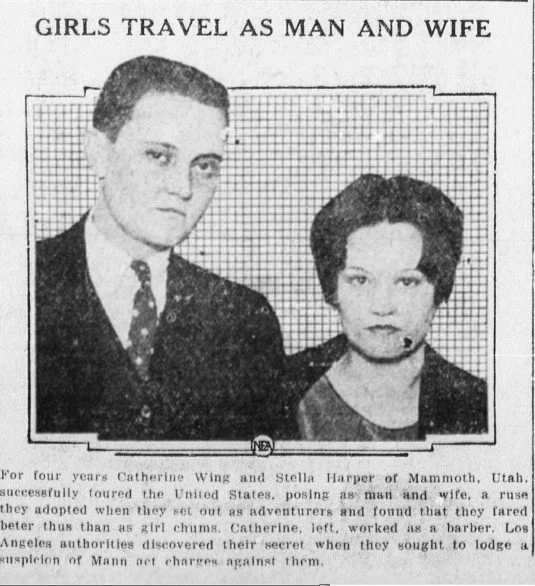

‘Kenneth Wing moved to Los Angeles in 1926 and began going by Kenneth Lisonbee (his mother's maiden name). He lived just around the corner from where he opened a barbershop on West Manchester Avenue. Now 23, he met 18-year-old Eileen Garnett (from Missouri) and they fell in love. They married in Santa Ana on May 24, 1927. After they married, Eileen's parents moved in with them, discovered Kenneth's "true sex," and not only compelled the couple to break up, but reported Kenneth's deceit to authorities. Apparently, Kenneth returned to Utah, where he met and fell in love with Estella Harper. Living as a married couple, they went back to LA, but neighbors there reported that they were not married, so Kenneth was arrested in January 1929 under the Mann Act (aka the White Slave Traffic Act of 1910), which prosecuted men for taking women across state lines for immoral purposes. However, when it was discovered that Kenneth had been assigned female at birth, the state's case fell apart. But then discovering that Kenneth had falsified a marriage license (by presenting as a man) in 1927 to marry Eileen Garnett, charges were refiled against him, but eventually dropped. But not until the case made nation headlines, including in Utah (The Salt Lake Tribune, January 1929, p. 9).

‘The couple moved back to Utah, where they lived with Kenneth's parents, who apparently had no problem with Kenneth's male identity. However, in the 1930 Census, Kenneth is listed in his parents' household as Katherine R. Wing (female), with partner Estella Harper as a boarder there.’

Kenneth died in Twentynine Palms, San Bernadino County, California in 1991. The “California's Death Index,” writes O’Donovan, “has him listed as both Kennie R. Wing and Katherine R. Lisonbee.” (See also this biography by Elisa Rolle).